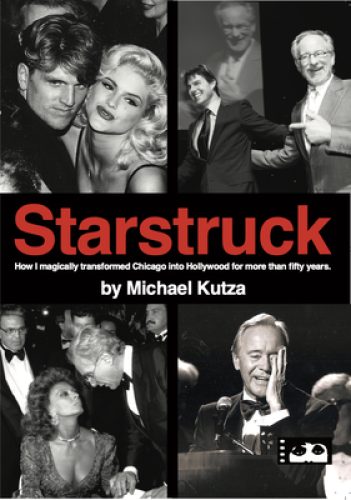

The subhead for Michael Kutza’s autobiography really says it all: “How I magically transformed Chicago into Hollywood for more than fifty years.” Centered on a cover that includes shots of Tom Cruise, Sophia Loren, Jack Lemmon, and Anna Nicole Smith (?), Kutza’s intention is clear: This is a book about star power and how the founder of the Chicago International Film Festival reached up and grabbed some of it for the Windy City, refusing to buy into the belief that celebrities would only appear in coastal cities. Before Sundance or Toronto, Kutza had a dream of a Chicago event that would garner international attention, and he founded CIFF in 1964 with Colleen Moore and King Vidor—yes, the silent movie star and director. Kutza clearly has a lot of stories to tell over five decades of rubbing shoulders with some of the most glamorous Hollywood personalities in history, and it’s interesting to see how that drove his management of CIFF, and how his ascendance intersected with Roger Ebert’s.

Kutza’s book is basically a collection of anecdotes, stories about his time with the festival, loosely arranged into chapters that are broken up by pages of black-and-white photos. He offers some personal details, but he’s way more focused on his festival, more excited when he’s sharing salacious details about a star’s behavior than revealing something about himself. Say what you will about CIFF, there’s no denying that Michael Kutza poured his heart and soul into this event, producing one of the longest-running film festivals anywhere, and shaping the film scene in ways that are underrated around the world. For example, he makes clear in his sixth chapter how important it was to him to be first, to be the festival that elevated new talent. At that first festival in 1965, he had a documentary called “The People vs. Paul Crump” by a young director named William Friedkin. In 1967, two years later, they programmed a little film called “I Call First,” which would later be re-titled “Who’s That Knocking at My Door,” and the rest is history, not just because the world now knew about Martin Scorsese, but because Roger Ebert did. Ebert has written about seeing “I Call First” at CIFF, immediately realizing he was watching “The American Fellini,” and the relationship between Scorsese and Ebert may not have unfolded in exactly the same way without Michael Kutza.

Ebert plays a major role in Starstruck, featured in numerous photos. (Chaz too gets a photo with the deserving caption: “Chaz Ebert, Roger Ebert’s dynamic and lovely wife.”) Kutza also devotes a chapter to critics of the Windy City and the world, noting how Roger’s first job out of college was to cover CIFF for the Chicago Sun-Times, and how Kutza invited Roger to the Tehran Film Festival and the Venice Film Festival. He would use Roger in intros and Q&As, and graciously notes that he “went out of his way to help put us on the map and give us legitimacy in a way no other critic could.” Kutza is less generous to some other local critics (and the entire institution really), but I’ll leave my colleagues to find those passages for themselves. Still, it’s nice to read about how Roger’s and Kutza’s legacies intertwined, and to see how much respect Michael clearly had for Roger.

As much as Kutza loves to name-drop the legends who have come through CIFF, he enjoys a juicy story about them even more. Kutza bounces around in time from chapter to chapter like he’s thinking up new stories to tell at a party. He tells of Sharon Stone demanding a limo driver be fired; Lauren Bacall turning into a grouch after Bill Kurtis mentioned on-stage that it was her 75th birthday; Charlton Heston crashing to the stage after sitting on a chair arm; Liv Ullman telling her husband she wanted a divorce right in front of Kutza. His response is indicative of a showman’s attitude: “Look, let’s solve the film problem first, then you two can work the other thing out later.” For people like Kutza, the show must always go on.

And that’s really the strength of Starstruck for anyone who’s not interested in the pages of black-and-white photos or the casual prose: this is the story of a man who wanted to bring the glitz and glamour of Hollywood to his hometown, and would do anything to make that happen. A lot has been written about CIFF over the years and it does feel like there’s another book to be written that brings in more viewpoints on the successes and failures of the event, but that’s not this book. This book is about dedication to a nearly impossible dream. And while I wish it was a little sharper in its wording and a little less shapeless in its form, there’s something undeniably admirable about anyone who can play a game as tough as the film festival circuit for five decades. Kutza didn’t just play the game. He’d love to raise a glass and tell you about how he rewrote the rules of it. It’s certainly a hell of a story.

The subhead for Michael Kutza’s autobiography really says it all: “How I magically transformed Chicago into Hollywood for more than fifty years.” Centered on a cover that includes shots of Tom Cruise, Sophia Loren, Jack Lemmon, and Anna Nicole Smith (?), Kutza’s intention is clear: This is a book about star power and how the founder of the Chicago International Film Festival reached up and grabbed some of it for the Windy City, refusing to buy into the belief that celebrities would only appear in coastal cities. Before Sundance or Toronto, Kutza had a dream of a Chicago event that would garner international attention, and he founded CIFF in 1964 with Colleen Moore and King Vidor—yes, the silent movie star and director. Kutza clearly has a lot of stories to tell over five decades of rubbing shoulders with some of the most glamorous Hollywood personalities in history, and it’s interesting to see how that drove his management of CIFF, and how his ascendance intersected with Roger Ebert’s. Kutza’s book is basically a collection of anecdotes, stories about his time with the festival, loosely arranged into chapters that are broken up by pages of black-and-white photos. He offers some personal details, but he’s way more focused on his festival, more excited when he’s sharing salacious details about a star’s behavior than revealing something about himself. Say what you will about CIFF, there’s no denying that Michael Kutza poured his heart and soul into this event, producing one of the longest-running film festivals anywhere, and shaping the film scene in ways that are underrated around the world. For example, he makes clear in his sixth chapter how important it was to him to be first, to be the festival that elevated new talent. At that first festival in 1965, he had a documentary called “The People vs. Paul Crump” by a young director named William Friedkin. In 1967, two years later, they programmed a little film called “I Call First,” which would later be re-titled “Who’s That Knocking at My Door,” and the rest is history, not just because the world now knew about Martin Scorsese, but because Roger Ebert did. Ebert has written about seeing “I Call First” at CIFF, immediately realizing he was watching “The American Fellini,” and the relationship between Scorsese and Ebert may not have unfolded in exactly the same way without Michael Kutza. Ebert plays a major role in Starstruck, featured in numerous photos. (Chaz too gets a photo with the deserving caption: “Chaz Ebert, Roger Ebert’s dynamic and lovely wife.”) Kutza also devotes a chapter to critics of the Windy City and the world, noting how Roger’s first job out of college was to cover CIFF for the Chicago Sun-Times, and how Kutza invited Roger to the Tehran Film Festival and the Venice Film Festival. He would use Roger in intros and Q&As, and graciously notes that he “went out of his way to help put us on the map and give us legitimacy in a way no other critic could.” Kutza is less generous to some other local critics (and the entire institution really), but I’ll leave my colleagues to find those passages for themselves. Still, it’s nice to read about how Roger’s and Kutza’s legacies intertwined, and to see how much respect Michael clearly had for Roger. As much as Kutza loves to name-drop the legends who have come through CIFF, he enjoys a juicy story about them even more. Kutza bounces around in time from chapter to chapter like he’s thinking up new stories to tell at a party. He tells of Sharon Stone demanding a limo driver be fired; Lauren Bacall turning into a grouch after Bill Kurtis mentioned on-stage that it was her 75th birthday; Charlton Heston crashing to the stage after sitting on a chair arm; Liv Ullman telling her husband she wanted a divorce right in front of Kutza. His response is indicative of a showman’s attitude: “Look, let’s solve the film problem first, then you two can work the other thing out later.” For people like Kutza, the show must always go on. And that’s really the strength of Starstruck for anyone who’s not interested in the pages of black-and-white photos or the casual prose: this is the story of a man who wanted to bring the glitz and glamour of Hollywood to his hometown, and would do anything to make that happen. A lot has been written about CIFF over the years and it does feel like there’s another book to be written that brings in more viewpoints on the successes and failures of the event, but that’s not this book. This book is about dedication to a nearly impossible dream. And while I wish it was a little sharper in its wording and a little less shapeless in its form, there’s something undeniably admirable about anyone who can play a game as tough as the film festival circuit for five decades. Kutza didn’t just play the game. He’d love to raise a glass and tell you about how he rewrote the rules of it. It’s certainly a hell of a story. Buy a copy here. Read More