“If there were equality of opportunity in this business there would be fifteen Sidney Poitiers and ten to twelve Harry Belafontes. But there is not.”

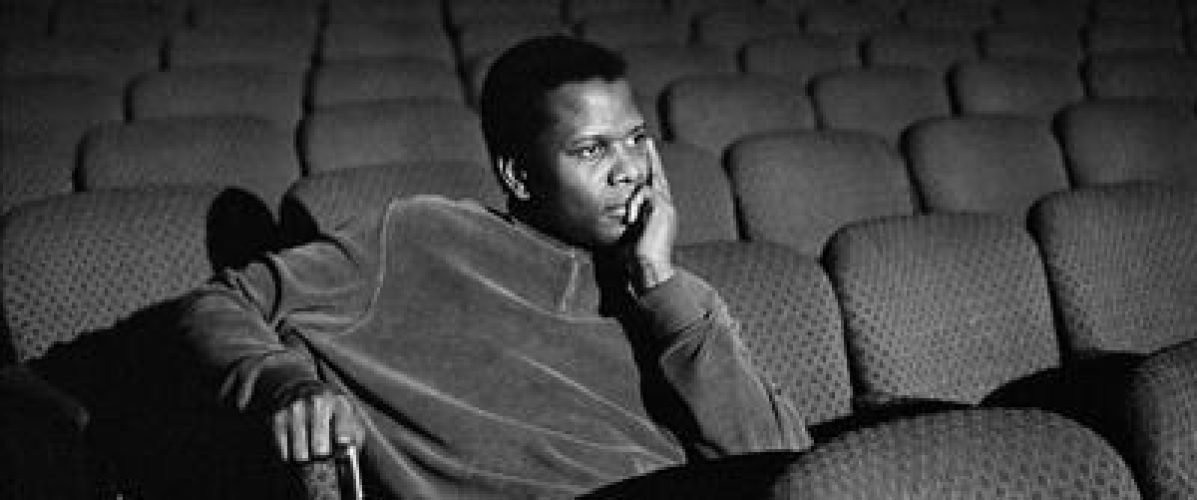

This truth is at the heart of “Sidney,” Reginald Hudlin’s new documentary about the Hollywood star Sidney Poitier. A chronological recounting of Poitier’s odds-defying breakthrough into the classic Hollywood system and becoming the first Black actor to win the Best Actor Oscar, this Oprah Winfrey-produced documentary does a wonderful job of maintaining the myth of Poitier as a trailblazer actor, director, activist, husband and father.

In a gorgeously filmed interview that will surely make fans of the late actor emotional, Poitier addresses the camera directly as he shares his origins on Cat Island in the Bahamas. Born two months early, his father was ready to bury him in a shoebox, but his mother sought out a soothsayer to assure her that her youngest son would have a bright future. This knowledge that he was supposed to die before he even lived pushed Poitier to live his life with gusto. Poitier attributes everything he became as a man to the foundation laid by his parents. His mother’s compassion and his father’s belief that the measure of a man is found in his ability to take care of his children.

Along with Poitier’s oral history of his own childhood in the Bahamas, teenage years facing racism in Jim Crow Miami, and early days struggling to break into the American Negro Theatre in Harlem, the documentary features talking head style conversations with those who knew him and those who were inspired by him. This includes interviews with his daughters, his ex-wife Juanita Hardy, his widow Joanna Shimkus, historian Nelson George, biographer Aram Goudsouzia, and actors Morgan Freeman, Halle Berry, and Denzel Washington.

While it’s refreshing to hear from Hardy and his daughters from his first marriage, the darker aspects of his nine-year affair with his “Paris Blues” co-star Diahann Carroll is highly sanitized, the implosion of which is only addressed by Carroll through a short archival clip. It’s disingenuous to not include more of Carroll’s point of view about their tempestuous relationship. Especially when compared to the raw honesty with which Ethan Hawke’s recent documentary “The Last Movie Stars” explored the more complicated aspects of fellow “Paris Blues” co-stars Paul Newman and Joanne Woodward’s affair, one that blew up two marriages before resulting in their long lasting marriage.

“Sidney” does a fine job outlining Poitier’s breakthrough into mainstream Hollywood movies and eventually into megastar status. Hudlin highlights the films—and filmmakers—who were brave enough to include a more realistic presentation of a Black man than previous decades in Hollywood, starting with Joseph L. Mankiewicz, who handpicked Poitier to play a young doctor in his drama “No Way Out.” From there the doc navigates the ways in which Poitier’s roles in films like “A Raisin In The Sun” and his Oscar-winning performance in “Lilies of the Field” paved a path for more nuanced portrayals of Black life in mainstream Hollywood cinema.

While the doc does explore the polarizing reception of Poitier within the Black community, especially in films like “The Defiant Ones” and “Guess Who’s Coming To Dinner,” it does so only fleetingly. James Baldwin, who wrote critically of both films in his book The Devil Finds Work, is shown in an archival clip—but his words are never used, with Hudlin either assuming the viewer is familiar with how Baldwin criticized the works, or doesn’t want those words to spoil his thesis that the films need to be understood within the context of when they were released. This ignores that Baldwin was criticizing them when they were released.

There’s also a lack of context around the other Black actors who did find some work in Hollywood. Paul Robeson gets a mention, along with the negative stereotypes portrayed by Mantan Moreland and Stepin Fetchit, but there’s no mention of serious actors like James Edwards, Canada Lee, or Juano Hernandez. However, the interviews with Freeman, Berry, and Washington expressing just how deeply Poitier’s breakthrough as a star in a way these others were unable to helps contextualize what made Poitier’s career success such a watershed moment for Black actors in the industry.

The doc fares best in its exploration of Poitier’s decades-long friendship with Harry Belafonte. The two met while working in the theater together, with Poitier getting his big break while filling in for Belafonte one night when he was called in for a last minute shift for his day job. Hudlin does an excellent job chronicling their friendship through those early days in the theater to their political work for civil rights in the 1960s to their collaboration together in Poitier’s directorial debut “Buck and the Preacher” in 1972. Archival clips of the two on talk shows like the “Dick Cavett Show” allows their deep admiration—and playful rivalry—to shine through even decades later.

Poitier’s impact as a director is briefly explored in contrast with the Blaxploitation era films at the same time. Barbra Streisand explains why she, Poitier, and Newman created the production company First Artists in order to have more control of their projects. Not only did Poitier shine as a director of comedies, he also made sure those working behind the scenes in his productions were mostly Black. But again, the doc shirks exploring the more complicated aspects of Poitier’s directorial output. Namely, the many films he directed starring Bill Cosby.

“It’s difficult when you’re carrying other people’s dreams,” Poitier tells Oprah at her 42nd birthday party. Herein lies the challenge of telling a man like Poitier’s story. Do you print the legend or do you delve deeper into the flaws? It’s a balancing act for sure, and one that Hudlin doesn’t quite pull off.

“Sidney” works more as an explainer for why Sidney Poitier remains such an important figure in American history—not just Hollywood history—than it does as a warts-and-all biography of Sidney the man. It may be too soon for that kind of documentary about Poitier, whose impact looms large over a Hollywood that still doesn’t have the equity of opportunity he opined some 50 years ago.

This review was filed from the Toronto International Film Festival on September 10th. “Sidney” will premiere in select theaters and on Apple TV+ on September 23rd.

“If there were equality of opportunity in this business there would be fifteen Sidney Poitiers and ten to twelve Harry Belafontes. But there is not.” This truth is at the heart of “Sidney,” Reginald Hudlin’s new documentary about the Hollywood star Sidney Poitier. A chronological recounting of Poitier’s odds-defying breakthrough into the classic Hollywood system and becoming the first Black actor to win the Best Actor Oscar, this Oprah Winfrey-produced documentary does a wonderful job of maintaining the myth of Poitier as a trailblazer actor, director, activist, husband and father. In a gorgeously filmed interview that will surely make fans of the late actor emotional, Poitier addresses the camera directly as he shares his origins on Cat Island in the Bahamas. Born two months early, his father was ready to bury him in a shoebox, but his mother sought out a soothsayer to assure her that her youngest son would have a bright future. This knowledge that he was supposed to die before he even lived pushed Poitier to live his life with gusto. Poitier attributes everything he became as a man to the foundation laid by his parents. His mother’s compassion and his father’s belief that the measure of a man is found in his ability to take care of his children. Along with Poitier’s oral history of his own childhood in the Bahamas, teenage years facing racism in Jim Crow Miami, and early days struggling to break into the American Negro Theatre in Harlem, the documentary features talking head style conversations with those who knew him and those who were inspired by him. This includes interviews with his daughters, his ex-wife Juanita Hardy, his widow Joanna Shimkus, historian Nelson George, biographer Aram Goudsouzia, and actors Morgan Freeman, Halle Berry, and Denzel Washington. While it’s refreshing to hear from Hardy and his daughters from his first marriage, the darker aspects of his nine-year affair with his “Paris Blues” co-star Diahann Carroll is highly sanitized, the implosion of which is only addressed by Carroll through a short archival clip. It’s disingenuous to not include more of Carroll’s point of view about their tempestuous relationship. Especially when compared to the raw honesty with which Ethan Hawke’s recent documentary “The Last Movie Stars” explored the more complicated aspects of fellow “Paris Blues” co-stars Paul Newman and Joanne Woodward’s affair, one that blew up two marriages before resulting in their long lasting marriage. “Sidney” does a fine job outlining Poitier’s breakthrough into mainstream Hollywood movies and eventually into megastar status. Hudlin highlights the films—and filmmakers—who were brave enough to include a more realistic presentation of a Black man than previous decades in Hollywood, starting with Joseph L. Mankiewicz, who handpicked Poitier to play a young doctor in his drama “No Way Out.” From there the doc navigates the ways in which Poitier’s roles in films like “A Raisin In The Sun” and his Oscar-winning performance in “Lilies of the Field” paved a path for more nuanced portrayals of Black life in mainstream Hollywood cinema. While the doc does explore the polarizing reception of Poitier within the Black community, especially in films like “The Defiant Ones” and “Guess Who’s Coming To Dinner,” it does so only fleetingly. James Baldwin, who wrote critically of both films in his book The Devil Finds Work, is shown in an archival clip—but his words are never used, with Hudlin either assuming the viewer is familiar with how Baldwin criticized the works, or doesn’t want those words to spoil his thesis that the films need to be understood within the context of when they were released. This ignores that Baldwin was criticizing them when they were released. There’s also a lack of context around the other Black actors who did find some work in Hollywood. Paul Robeson gets a mention, along with the negative stereotypes portrayed by Mantan Moreland and Stepin Fetchit, but there’s no mention of serious actors like James Edwards, Canada Lee, or Juano Hernandez. However, the interviews with Freeman, Berry, and Washington expressing just how deeply Poitier’s breakthrough as a star in a way these others were unable to helps contextualize what made Poitier’s career success such a watershed moment for Black actors in the industry. The doc fares best in its exploration of Poitier’s decades-long friendship with Harry Belafonte. The two met while working in the theater together, with Poitier getting his big break while filling in for Belafonte one night when he was called in for a last minute shift for his day job. Hudlin does an excellent job chronicling their friendship through those early days in the theater to their political work for civil rights in the 1960s to their collaboration together in Poitier’s directorial debut “Buck and the Preacher” in 1972. Archival clips of the two on talk shows like the “Dick Cavett Show” allows their deep admiration—and playful rivalry—to shine through even decades later. Poitier’s impact as a director is briefly explored in contrast with the Blaxploitation era films at the same time. Barbra Streisand explains why she, Poitier, and Newman created the production company First Artists in order to have more control of their projects. Not only did Poitier shine as a director of comedies, he also made sure those working behind the scenes in his productions were mostly Black. But again, the doc shirks exploring the more complicated aspects of Poitier’s directorial output. Namely, the many films he directed starring Bill Cosby. “It’s difficult when you’re carrying other people’s dreams,” Poitier tells Oprah at her 42nd birthday party. Herein lies the challenge of telling a man like Poitier’s story. Do you print the legend or do you delve deeper into the flaws? It’s a balancing act for sure, and one that Hudlin doesn’t quite pull off. “Sidney” works more as an explainer for why Sidney Poitier remains such an important figure in American history—not just Hollywood history—than it does as a warts-and-all biography of Sidney the man. It may be too soon for that kind of documentary about Poitier, whose impact looms large over a Hollywood that still doesn’t have the equity of opportunity he opined some 50 years ago. This review was filed from the Toronto International Film Festival on September 10th. “Sidney” will premiere in select theaters and on Apple TV+ on September 23rd. Read More