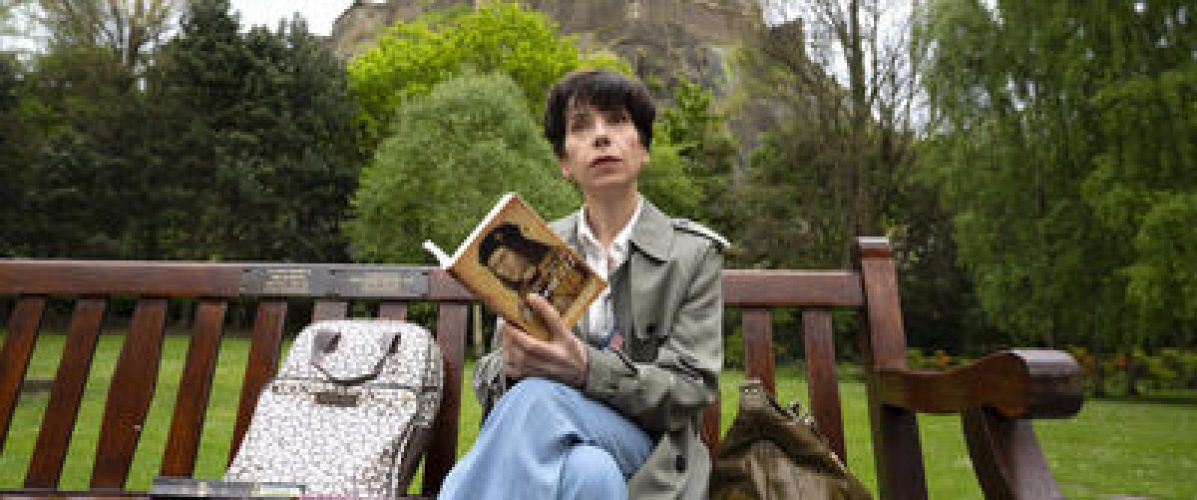

Philippa Langley (Sally Hawkins) sits in a coffee shop reading a book. A pamphlet falls out. She reads: “What can YOU do? Join us as we work towards changing the way history views this much-maligned monarch!” The “much-maligned monarch” is Richard III. Sparked by curiosity, Philippa—not an academic or historian—follows the pamphlet’s call and attends her first meeting of the Richard III Society, held in the back of a pub. The rest is history.

“The Lost King,” directed by Stephen Frears, is based on a true story, Philippa Langley’s own (detailed in her excellent book The Search for Richard III). If you were following along with events in 2012, Langley somehow, as a private citizen unconnected to a university or a rich foundation, commissioned an archaeological dig in a random car park in Leicester, hoping to find Richard III’s grave. Relying on medieval maps and accounts of Richard III’s burial from people who were actually there in 1485, she narrowed down the possible location. The dig commenced. Amazingly, “they” found him on the first day of the dig. There he was, his intact skeleton, complete with a scoliosis-curved spine and fatal head wound. Instantly recognizable to the naked eye. Incredible!

This was the culmination of a long, long fight. The “Ricardians,” as they call themselves, didn’t believe the story that Richard’s body was dumped into a river following the battle on Bosworth field. Ricardians want to correct the historical record and rehabilitate the reputation of Richard III, who is generally seen as not only a villain but a “usurper,” not a legitimate king at all. The Ricardians dispute this narrative, and they come with receipts. For example, the city of York responded to the news of Richard’s death with: “King Richard late mercifully reigning over us was through great treason piteously slain and murdered, to the great heaviness of this city.” This is hardly “Ding Dong the Witch is dead.” Not one word about his tyranny? Not one word about the princes in the tower? Not one word about … anything? Shakespeare is mainly to blame for Richard’s reputation as an almost cartoonish villain, having his Richard say at one point:

“And thus I clothe my naked villainy

With old odd ends stolen out of holy writ;

And seem a saint, when most I play the devil.”

Shakespeare took his interpretation from the existing chronicles (after all, Richard died only 100 years before Shakespeare wrote his play). The “usurper”‘s reputation has been in the hands of his enemies ever since.

“The Lost King” walks you through it, adding a couple of whimsical details, as well as pumping up Philippa’s emotional drama, centralizing her in the story. This is meant to “personalize” it, to ground it in one woman’s journey towards actualization. These details work in a fairly obvious way, detracting from the interest already inherent in this 500-year-old murder mystery. For example, Philippa is basically “stalked” by an apparition, Richard III himself (Harry Lloyd), complete with a flowing purple cape and golden crown. He shows up everywhere, beseeching her with his eyes to help him. She speaks with him late at night. She asks him questions. When she asks if he murdered “the princes in the tower” (those vanished princes are key!), he stalks off in a huff, hurt that she would even ask. It’s a bit corny. Philippa’s two small sons think she’s going mad. Her husband (Steve Coogan, who produced) is also worried and maybe slightly jealous. “The Lost King” positions itself as a love affair between Philippa and Richard, an unnecessary emotional embellishment, as though passionate engagement with history isn’t enough. The heightened emotionality is intensified by Alexandre Desplat’s score; Sally Hawkins plays it on the trembling edge of tragic romance.

Philippa faces resistance as she conducts her own investigation. She makes appeals for funding, and she reaches out to an archaeologist, showing him her research. She does a lot of reading, but we’re never shown what actually convinces her the narrative is wrong. She receives “signs” (a huge letter ‘R” in the car park, etc.) and follows her gut. I’m more impressed with the legwork done by all, the ability to read between the lines of highly biased historical records to try to approximate what really happened. Feelings are great, but you need more than “feelings” to dig up a lost king.

The recent “The Dig” tells a similar true story and keeps the focus on the legwork done without sacrificing character interest. Edith Pretty (Casey Mulligan), a woman interested in archaeology, is convinced there might be buried treasure on her land. She’s right. There is. The “Sutton Hoo find” is one of the most significant archaeological discoveries of all time, and it was all spearheaded by this sickly woman with no connections. “The Dig,” though, unlike “The Lost King,” doesn’t show Edith’s field filled with ghostly apparitions of wandering Anglo-Saxons wearing golden helmets, beseeching Edith to tell the story of their civilization. It focuses on the dig itself, the hard work, the research, and the knowledge required to make such discoveries. “The Lost King” gets sidetracked.

Still, it’s a great story!

Back in college, I went through a small Ricardian phase. I didn’t go too deep into it, I just wondered if there might be more to the story. I remember being haunted by John Everett Millais’ famous painting The Two Princes Edward and Richard in the Tower, 1483: those two blonde boys wearing black velvet, huddled together, looking around them fearfully. It’s the most chilling part of the story, if true. What happened to those boys? Nobody seems to know to this day. Ask the question on the internet, though, and get ready to lose hours of your life in well-researched speculation.

What is true, and what isn’t? One of the Ricardians tells Philippa early on, “If you get in quick with the first lie and then repeat it enough, it becomes history.”

Now playing in theaters.

Philippa Langley (Sally Hawkins) sits in a coffee shop reading a book. A pamphlet falls out. She reads: “What can YOU do? Join us as we work towards changing the way history views this much-maligned monarch!” The “much-maligned monarch” is Richard III. Sparked by curiosity, Philippa—not an academic or historian—follows the pamphlet’s call and attends her first meeting of the Richard III Society, held in the back of a pub. The rest is history. “The Lost King,” directed by Stephen Frears, is based on a true story, Philippa Langley’s own (detailed in her excellent book The Search for Richard III). If you were following along with events in 2012, Langley somehow, as a private citizen unconnected to a university or a rich foundation, commissioned an archaeological dig in a random car park in Leicester, hoping to find Richard III’s grave. Relying on medieval maps and accounts of Richard III’s burial from people who were actually there in 1485, she narrowed down the possible location. The dig commenced. Amazingly, “they” found him on the first day of the dig. There he was, his intact skeleton, complete with a scoliosis-curved spine and fatal head wound. Instantly recognizable to the naked eye. Incredible! This was the culmination of a long, long fight. The “Ricardians,” as they call themselves, didn’t believe the story that Richard’s body was dumped into a river following the battle on Bosworth field. Ricardians want to correct the historical record and rehabilitate the reputation of Richard III, who is generally seen as not only a villain but a “usurper,” not a legitimate king at all. The Ricardians dispute this narrative, and they come with receipts. For example, the city of York responded to the news of Richard’s death with: “King Richard late mercifully reigning over us was through great treason piteously slain and murdered, to the great heaviness of this city.” This is hardly “Ding Dong the Witch is dead.” Not one word about his tyranny? Not one word about the princes in the tower? Not one word about … anything? Shakespeare is mainly to blame for Richard’s reputation as an almost cartoonish villain, having his Richard say at one point: “And thus I clothe my naked villainyWith old odd ends stolen out of holy writ;And seem a saint, when most I play the devil.” Shakespeare took his interpretation from the existing chronicles (after all, Richard died only 100 years before Shakespeare wrote his play). The “usurper”‘s reputation has been in the hands of his enemies ever since. “The Lost King” walks you through it, adding a couple of whimsical details, as well as pumping up Philippa’s emotional drama, centralizing her in the story. This is meant to “personalize” it, to ground it in one woman’s journey towards actualization. These details work in a fairly obvious way, detracting from the interest already inherent in this 500-year-old murder mystery. For example, Philippa is basically “stalked” by an apparition, Richard III himself (Harry Lloyd), complete with a flowing purple cape and golden crown. He shows up everywhere, beseeching her with his eyes to help him. She speaks with him late at night. She asks him questions. When she asks if he murdered “the princes in the tower” (those vanished princes are key!), he stalks off in a huff, hurt that she would even ask. It’s a bit corny. Philippa’s two small sons think she’s going mad. Her husband (Steve Coogan, who produced) is also worried and maybe slightly jealous. “The Lost King” positions itself as a love affair between Philippa and Richard, an unnecessary emotional embellishment, as though passionate engagement with history isn’t enough. The heightened emotionality is intensified by Alexandre Desplat’s score; Sally Hawkins plays it on the trembling edge of tragic romance. Philippa faces resistance as she conducts her own investigation. She makes appeals for funding, and she reaches out to an archaeologist, showing him her research. She does a lot of reading, but we’re never shown what actually convinces her the narrative is wrong. She receives “signs” (a huge letter ‘R” in the car park, etc.) and follows her gut. I’m more impressed with the legwork done by all, the ability to read between the lines of highly biased historical records to try to approximate what really happened. Feelings are great, but you need more than “feelings” to dig up a lost king. The recent “The Dig” tells a similar true story and keeps the focus on the legwork done without sacrificing character interest. Edith Pretty (Casey Mulligan), a woman interested in archaeology, is convinced there might be buried treasure on her land. She’s right. There is. The “Sutton Hoo find” is one of the most significant archaeological discoveries of all time, and it was all spearheaded by this sickly woman with no connections. “The Dig,” though, unlike “The Lost King,” doesn’t show Edith’s field filled with ghostly apparitions of wandering Anglo-Saxons wearing golden helmets, beseeching Edith to tell the story of their civilization. It focuses on the dig itself, the hard work, the research, and the knowledge required to make such discoveries. “The Lost King” gets sidetracked. Still, it’s a great story! Back in college, I went through a small Ricardian phase. I didn’t go too deep into it, I just wondered if there might be more to the story. I remember being haunted by John Everett Millais’ famous painting The Two Princes Edward and Richard in the Tower, 1483: those two blonde boys wearing black velvet, huddled together, looking around them fearfully. It’s the most chilling part of the story, if true. What happened to those boys? Nobody seems to know to this day. Ask the question on the internet, though, and get ready to lose hours of your life in well-researched speculation. What is true, and what isn’t? One of the Ricardians tells Philippa early on, “If you get in quick with the first lie and then repeat it enough, it becomes history.” Now playing in theaters. Read More