Richard Davis’ story is a particularly American one, as director Ramin Bahrani notes in his feature documentary debut, “2nd Chance.” It’s full of self-aggrandizement and reinvention, good and bad guys, sincerity, and hypocrisy. The contradictions within the man who invented the modern bulletproof vest are stark; within his down-home demeanor, there are myriad examples of his desperation and deceit.

Davis is simultaneously fascinating and repulsive, as Bahrani reveals in his quietly observational style and understated questioning and narration. It’s when the director expands his scope that his film begins to feel unfocused and a little messy. Bahrani tries to connect Davis to more significant issues that have marked our country’s history over the past several decades, from the military-industrial complex to police brutality to the icky, inextricable link between sex and violence. Indeed, the director of “99 Homes” and “The White Tiger” has proven a driving interest in telling stories that shine a light on injustice and cruelty. But here, the result suggests he’s dipping his toe into these enormous subjects rather than getting his arms around them in a smart and satisfying way.

The most fascinating figure in “2nd Chance” is front and center from the beginning. When we first see Davis in archival footage, he’s shooting himself in the chest to demonstrate the protective power of the vest he’s designed. He’s matter-of-fact as he walks us through this harrowing act; we’ll learn that he’s done this 192 times in his life.

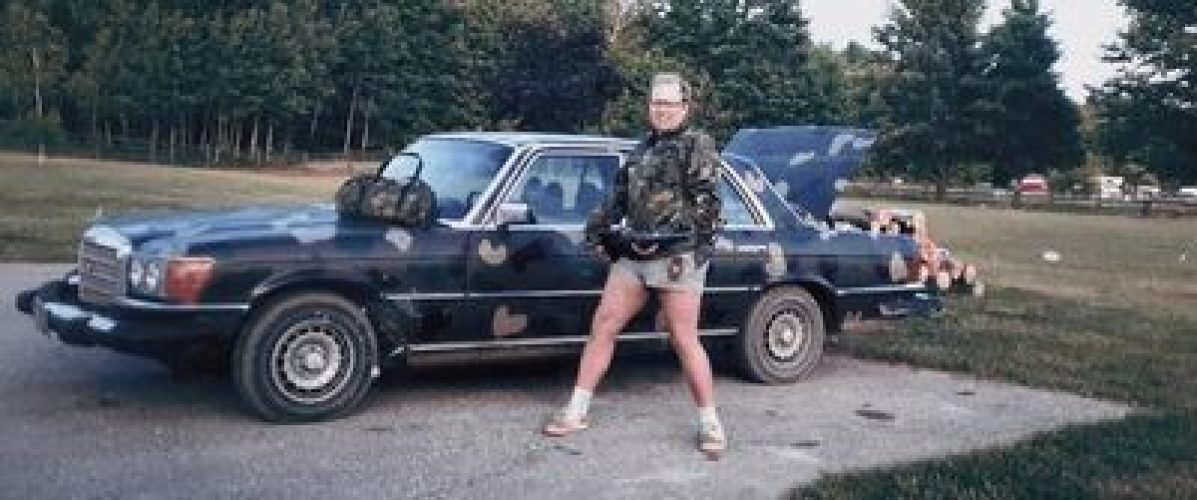

But the bespectacled Michigander isn’t just obsessed with weaponry. He’s also a showman and a filmmaker. His low-budget, pulpy pictures, which are intended as glorified infomercials for his former business, Second Chance, draw from the swaggering ethos of “Dirty Harry” in hilarious and appalling ways.

What’s consistent in all his propaganda, regardless of the medium, is that the bulletproof vest he created saves the day. Watching more recent interviews with him, as he sits on a comfy leather couch in his humble living room, you get the idea that he derives an authentic sense of pride in having saved hundreds of police officers’ lives. For all the shadiness we’ll discover about Davis down the line, there’s something earnest and pure about the sense of duty that defines him. Or did, for a time.

And yet his entire operation also was meant to instill fear in police officers that criminals were such an incessant threat, andthe only way to stay alive was to buy more of his product. In particular, 9/11 was a boon to his business, as it allowed him to expand his sales beyond individual police departments and into the larger United States military. The fact that he so giddily benefitted from so much unnecessary violence and suffering makes him kind of an abhorrent human being, an instinct he masks with a puckish sense of humor and an aw-shucks persona.

Both of his ex-wives speak to the narcissism that motivates him, which, shockingly, stems from his lifelong daddy issues. “Richard desperately needs to be loved by people,” one of them recalls wearily. And yet that fortified sense of self protects him from having to do too much self-examination about his many illegal and unethical decisions or the myriad lives he’s ruined.

So is he a sociopath? A compulsive liar? Or perhaps he’s just made the mistake of believing his own hype, and he’s surrounded himself with macho meatheads who are similarly obsessed with gun culture. Bahrani lets Davis speak for himself, and he rounds out the picture of this complicated figure with similarly unadorned but impactful discussions with former employees and colleagues and even Davis’ son, with whom he co-owns a new body armor business.

But it’s the interviews in the film’s epilogue that give this film greater depth and shading and elevate it to unexpected emotional heights. This big reveal packs a powerful punch, and it provides the film’s title with a whole new meaning.

Now playing in theaters.

Richard Davis’ story is a particularly American one, as director Ramin Bahrani notes in his feature documentary debut, “2nd Chance.” It’s full of self-aggrandizement and reinvention, good and bad guys, sincerity, and hypocrisy. The contradictions within the man who invented the modern bulletproof vest are stark; within his down-home demeanor, there are myriad examples of his desperation and deceit. Davis is simultaneously fascinating and repulsive, as Bahrani reveals in his quietly observational style and understated questioning and narration. It’s when the director expands his scope that his film begins to feel unfocused and a little messy. Bahrani tries to connect Davis to more significant issues that have marked our country’s history over the past several decades, from the military-industrial complex to police brutality to the icky, inextricable link between sex and violence. Indeed, the director of “99 Homes” and “The White Tiger” has proven a driving interest in telling stories that shine a light on injustice and cruelty. But here, the result suggests he’s dipping his toe into these enormous subjects rather than getting his arms around them in a smart and satisfying way. The most fascinating figure in “2nd Chance” is front and center from the beginning. When we first see Davis in archival footage, he’s shooting himself in the chest to demonstrate the protective power of the vest he’s designed. He’s matter-of-fact as he walks us through this harrowing act; we’ll learn that he’s done this 192 times in his life. But the bespectacled Michigander isn’t just obsessed with weaponry. He’s also a showman and a filmmaker. His low-budget, pulpy pictures, which are intended as glorified infomercials for his former business, Second Chance, draw from the swaggering ethos of “Dirty Harry” in hilarious and appalling ways. What’s consistent in all his propaganda, regardless of the medium, is that the bulletproof vest he created saves the day. Watching more recent interviews with him, as he sits on a comfy leather couch in his humble living room, you get the idea that he derives an authentic sense of pride in having saved hundreds of police officers’ lives. For all the shadiness we’ll discover about Davis down the line, there’s something earnest and pure about the sense of duty that defines him. Or did, for a time. And yet his entire operation also was meant to instill fear in police officers that criminals were such an incessant threat, andthe only way to stay alive was to buy more of his product. In particular, 9/11 was a boon to his business, as it allowed him to expand his sales beyond individual police departments and into the larger United States military. The fact that he so giddily benefitted from so much unnecessary violence and suffering makes him kind of an abhorrent human being, an instinct he masks with a puckish sense of humor and an aw-shucks persona. Both of his ex-wives speak to the narcissism that motivates him, which, shockingly, stems from his lifelong daddy issues. “Richard desperately needs to be loved by people,” one of them recalls wearily. And yet that fortified sense of self protects him from having to do too much self-examination about his many illegal and unethical decisions or the myriad lives he’s ruined. So is he a sociopath? A compulsive liar? Or perhaps he’s just made the mistake of believing his own hype, and he’s surrounded himself with macho meatheads who are similarly obsessed with gun culture. Bahrani lets Davis speak for himself, and he rounds out the picture of this complicated figure with similarly unadorned but impactful discussions with former employees and colleagues and even Davis’ son, with whom he co-owns a new body armor business. But it’s the interviews in the film’s epilogue that give this film greater depth and shading and elevate it to unexpected emotional heights. This big reveal packs a powerful punch, and it provides the film’s title with a whole new meaning. Now playing in theaters. Read More