The warm and engaging “Good Night Oppy” isn’t a Disney or Pixar movie, but a lot of times it feels like one. Directed by Ryan White (“The Keepers,” “The Case Against 8“), it’s a documentary about the mission to explore the surface of Mars with remote-controlled, unmanned robots, named Spirit and Opportunity. The mission started in 2003 and continued all the way through 2011. This was a surprise to the NASA scientists and engineers in charge, who had gone into it assuming that the robots might survive for a few months at best. Another surprise was how much emotion the humans invested in the robots, who are anthropomorphized by the NASA team (and the filmmakers) in the manner of lovable cartoon characters or “Star Wars” androids.

The routines and motivational rituals associated with Spirit and Opportunity (Oppy for short) contributed to the sense that these two long-necked metal things roving across the dusty ochre surface of Mars had personalities and could feel pain. Anthropomorphizing—the process of investing non-human things with human traits—is the real subject of this movie, and the focus of most of its drama.

The bulk of the running time consists of news, documentary, and home movie footage taken during the mission, plus interviews with key members of the team, but White and company got a mighty assist from state-of-the-art computer effects, which re-create the Mars mission in a style that recalls “Wall-E,” “The Martian,” and other science-fiction epics. Whenever there’s a cut to a closeup of the camera unit atop one of the rover’s long necks, we can’t help thinking of it as a face, and when one of them struggles to get out of a sandy sinkhole or change course despite a busted wheel, we root for them, just as we might root for Mustafa, Black Beauty, Lassie, R2-D2, or any other movie character who becomes an honorary person by having the audience’s emotions poured into them.

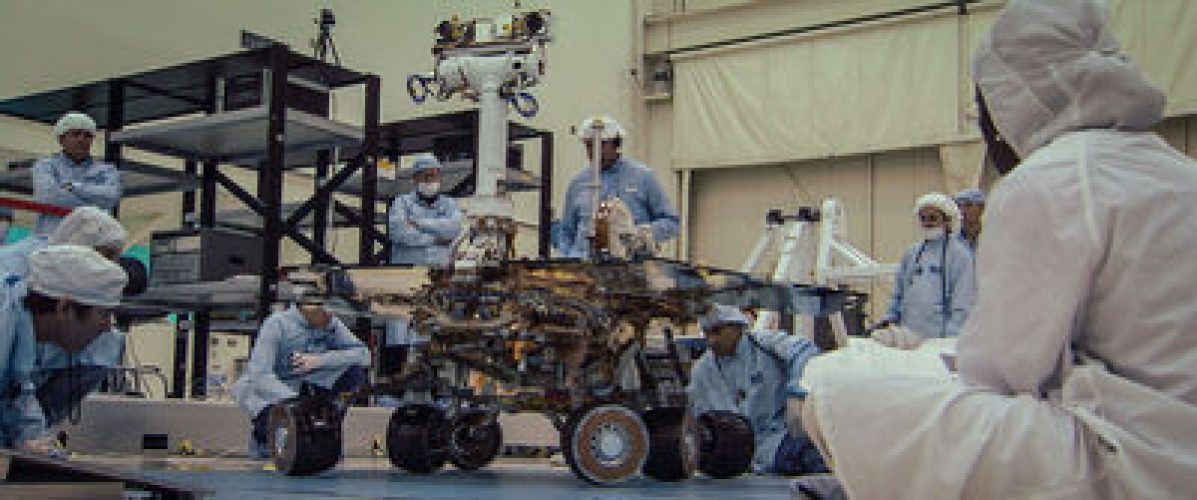

The interviewees describe what they were thinking and feeling as they tried to figure out how to get the robots from one place to another, and regularly maneuver them out of sand traps, or try to figure out a workaround for equipment failures and unforeseen geographical impediments. The story’s timespan is so compressed that occasionally seems to channel Christopher Nolan’s temporally relative “Interstellar.” When the NASA team pauses one of the machines’ journeys to test out solutions on a replica in the facility, the actual process might’ve taken months, but gets compacted into a couple of minutes’ worth of screen time. The passage of time is also explored by juxtaposing present-day interviews and archival footage. Some of the people involved in the mission were in their twenties or thirties back in the aughts and now have children, and/or have experienced decline and loss, and many of them are upfront in describing their time with Spirit and Oppy as the highlight of their lives.

To get across the magnitude of what his subjects saw and did, White pours on the commercial filmmaking devices from start to finish, in the manner of fun-for-all-ages summer blockbusters that used to dominate the box office in the 1980s and ’90s, and that were often produced (and occasionally directed) by Steven Spielberg or George Lucas. Sure enough, Spielberg’s company Amblin is one of the producers here; the effects are by the company Lucas founded, Industrial Light and Magic; and the score by Blake Neely (“The Pacific,” also an Ambln production) has that John Williams magic-and-wonder vibe.

“Good Night Oppy” lays the Spielberg-Lucas-Pixar elements on a bit thicker than it probably needed to, given the authentic emotions expressed by the interviewees (tears flow, a lot). If cereal is already sweet, it doesn’t require more sugar. But everyone involved in both the Mars mission and the film comes across as so fundamentally decent that the style seems of-a-piece with the story being told. (The hit pop songs interspersed through the tale—including “Walking on Sunshine” and “Here Comes the Sun”—aren’t just there to prime the viewer’s tear ducts: they’re the same ones that the NASA team chose to “wake up” the robots after their power-down periods.)

“Good Night Oppy” is light on scientific details about the machines and their purpose, but it does a fine job of showing how the act of investing oneself in mission-specific machines can lead people to think of them as friends, and become upset when challenges or misfortunes befall them. It’s inevitable that this story would eventually end with Spirit and Oppy succumbing to old age and interplanetary wear-and-tear (nothing lasts forever), but when it happens, twice, we grieve for them, just as their handlers did, and witnesses who compare the robots’ technical problems to arthritis or Alzheimers’ have good reason for reaching for those analogies: they make things make sense.

“Good Night Oppy” may be especially resonant for younger viewers who are interested in science but might not yet realize that there’s more to it than crunching numbers and drawing charts. The Mars team all have the zeal of true believers, and as the story unfolds, we see the immense focus and resilience that it takes to plan, execute, and prolong a large-scale project, as well as the ultimately positive feelings that everyone involved carried with them after it was done.

The warm and engaging “Good Night Oppy” isn’t a Disney or Pixar movie, but a lot of times it feels like one. Directed by Ryan White (“The Keepers,” “The Case Against 8”), it’s a documentary about the mission to explore the surface of Mars with remote-controlled, unmanned robots, named Spirit and Opportunity. The mission started in 2003 and continued all the way through 2011. This was a surprise to the NASA scientists and engineers in charge, who had gone into it assuming that the robots might survive for a few months at best. Another surprise was how much emotion the humans invested in the robots, who are anthropomorphized by the NASA team (and the filmmakers) in the manner of lovable cartoon characters or “Star Wars” androids. The routines and motivational rituals associated with Spirit and Opportunity (Oppy for short) contributed to the sense that these two long-necked metal things roving across the dusty ochre surface of Mars had personalities and could feel pain. Anthropomorphizing—the process of investing non-human things with human traits—is the real subject of this movie, and the focus of most of its drama. The bulk of the running time consists of news, documentary, and home movie footage taken during the mission, plus interviews with key members of the team, but White and company got a mighty assist from state-of-the-art computer effects, which re-create the Mars mission in a style that recalls “Wall-E,” “The Martian,” and other science-fiction epics. Whenever there’s a cut to a closeup of the camera unit atop one of the rover’s long necks, we can’t help thinking of it as a face, and when one of them struggles to get out of a sandy sinkhole or change course despite a busted wheel, we root for them, just as we might root for Mustafa, Black Beauty, Lassie, R2-D2, or any other movie character who becomes an honorary person by having the audience’s emotions poured into them. The interviewees describe what they were thinking and feeling as they tried to figure out how to get the robots from one place to another, and regularly maneuver them out of sand traps, or try to figure out a workaround for equipment failures and unforeseen geographical impediments. The story’s timespan is so compressed that occasionally seems to channel Christopher Nolan’s temporally relative “Interstellar.” When the NASA team pauses one of the machines’ journeys to test out solutions on a replica in the facility, the actual process might’ve taken months, but gets compacted into a couple of minutes’ worth of screen time. The passage of time is also explored by juxtaposing present-day interviews and archival footage. Some of the people involved in the mission were in their twenties or thirties back in the aughts and now have children, and/or have experienced decline and loss, and many of them are upfront in describing their time with Spirit and Oppy as the highlight of their lives. To get across the magnitude of what his subjects saw and did, White pours on the commercial filmmaking devices from start to finish, in the manner of fun-for-all-ages summer blockbusters that used to dominate the box office in the 1980s and ’90s, and that were often produced (and occasionally directed) by Steven Spielberg or George Lucas. Sure enough, Spielberg’s company Amblin is one of the producers here; the effects are by the company Lucas founded, Industrial Light and Magic; and the score by Blake Neely (“The Pacific,” also an Ambln production) has that John Williams magic-and-wonder vibe. “Good Night Oppy” lays the Spielberg-Lucas-Pixar elements on a bit thicker than it probably needed to, given the authentic emotions expressed by the interviewees (tears flow, a lot). If cereal is already sweet, it doesn’t require more sugar. But everyone involved in both the Mars mission and the film comes across as so fundamentally decent that the style seems of-a-piece with the story being told. (The hit pop songs interspersed through the tale—including “Walking on Sunshine” and “Here Comes the Sun”—aren’t just there to prime the viewer’s tear ducts: they’re the same ones that the NASA team chose to “wake up” the robots after their power-down periods.) “Good Night Oppy” is light on scientific details about the machines and their purpose, but it does a fine job of showing how the act of investing oneself in mission-specific machines can lead people to think of them as friends, and become upset when challenges or misfortunes befall them. It’s inevitable that this story would eventually end with Spirit and Oppy succumbing to old age and interplanetary wear-and-tear (nothing lasts forever), but when it happens, twice, we grieve for them, just as their handlers did, and witnesses who compare the robots’ technical problems to arthritis or Alzheimers’ have good reason for reaching for those analogies: they make things make sense. “Good Night Oppy” may be especially resonant for younger viewers who are interested in science but might not yet realize that there’s more to it than crunching numbers and drawing charts. The Mars team all have the zeal of true believers, and as the story unfolds, we see the immense focus and resilience that it takes to plan, execute, and prolong a large-scale project, as well as the ultimately positive feelings that everyone involved carried with them after it was done. Read More