Ever since I took my family to see writer/director Rodrigo García’s “Nine Lives” at Chicago’s Landmark Century Centre Cinema per Roger Ebert’s recommendation in 2005, the picture has always had a coveted spot on my top ten list of all-time favorite films. When Alfred Hitchcock attempted to craft a film that would be nearly devoid of cuts in “Rope,” the technique was unheard of in 1948. “Nine Lives” was released a year prior to Alfonso Cuarón’s great “Children of Men,” which demonstrated the visceral power of long takes courtesy of cinematographer Emmanuel Lubezki, whose tour de force achievement foreshadowed the subsequent work that would earn him three consecutive Oscars. In contrast, cinematographer Xavier Grobet’s lensing of “Nine Lives” is much more subtle in its brilliance. Like “Rope,” the film consists of nine takes, yet in this case, each take is a self-contained vignette that follows a woman during a pivotal moment in her life.

For decades, “Rope” had been deemed a misfire not only by critics and colleagues, but by Hitchcock himself, who referred to it as a nonsensical “stunt.” Even Donald Spoto, one of the most vital Hitchcock historians, claimed that the long takes in “Rope” contradicted “the basic nature of film itself,” though in The Art of Alfred Hitchcock, he goes on to indirectly illuminate the film’s genius. He mentions “Perpetual Movement No. 1,” the song composed by Francis Poulenc, that is played on the piano by Philip (Farley Granger), a closeted man who committed murder with his lover, Brandon (John Dall), a la Leopold and Loeb. Philip’s former teacher, Rupert (James Stewart), suspects foul play and approaches Philip at the piano, switching on a lamp that serves as an interrogation light. His conversation with Philip goes around in circles, thus mirroring the composition’s repetitious melody. Rupert then turns on a metronome that mechanically ticks down the seconds until Philip inevitably spills the beans. “The song is appropriate, perhaps, not only because the camera is in perpetual motion throughout ‘Rope,’ but because, ironically, the inner state of the principal characters is in an endless cycle of only apparent movement which is in itself a spiritual stasis,” writes Spoto.

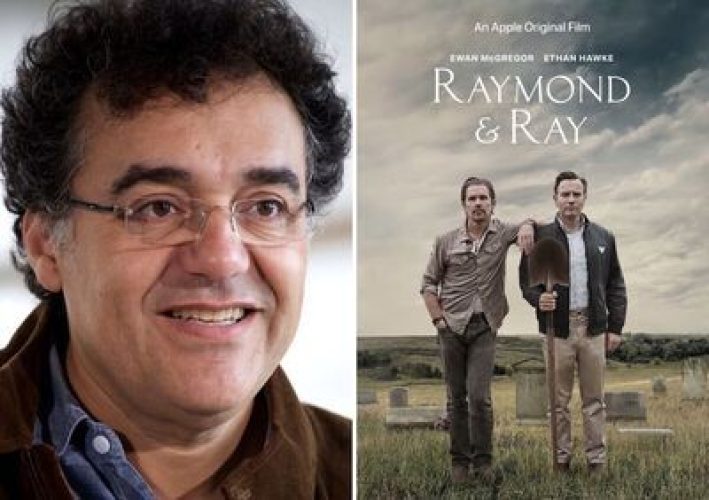

That sense of stasis is felt by all of the characters in “Nine Lives,” who find themselves trapped in situations that have stagnated their growth. The morning after his latest film, “Raymond & Ray,” screened at the Chicago International Film Festival, García took time to speak with me not only about his new movie, but “Nine Lives” as well. I told him that the latter film demonstrated to me, more than any other, how a short vignette can have the same rich texture and profound impact as a feature, which he affirmed was his ambition with the picture.

“You can tell a lot in ten, twelve minutes,” García said. “I see a lot of shorts, especially by younger people, that are impressionistic, but as long as you have the problem in minute one, you have a lot of time.”

My favorite scene features Robin Wright as a pregnant wife who runs into her former flame (Jason Isaacs) at the supermarket. As they talk, they settle into the playful rhythms of their past courtship, strolling down aisles that were built for couples to walk down side by side. Yet the coziness turns claustrophobic as Wright awakens to reality, as if breaking out of a trance. When Isaacs asks Wright for her husband’s name, she resists, explaining, “If I say his name to you right now, I won’t know if I’m coming or going.” One aspect of the film that becomes clearer upon repeat viewings is the way in which each woman’s story echoes throughout the surrounding vignettes. The first scene establishes the recurring theme of imprisonment by focusing on a mother (Elpidia Carrillo) in jail.

Later on, we see a budding adult (Amanda Seyfried) who is encouraged by her parents to leave home and “spread her wings,” despite the fact that her father (Ian McShane) suffers from a debilitating illness, and her mother (Sissy Spacek) is teetering on the brink of exhaustion. Faced with her childhood home haunted by memories of abuse, a tormented woman (LisaGay Hamilton) exclaims, “This place is a f—king graveyard,” a line that eerily hints at the setting for the film’s final scene. The lyrics of a childhood song Hamilton recites with her sister, “We are made of dreams and bones,” turn up again in the film’s warmest segment, as a patient (Kathy Baker) grows temperamental while preparing for her mastectomy. “I’m so angry with you,” she rants at her husband (Joe Mantegna). “What did I do?” he asks. “I don’t know, ever since I was diagnosed, I’ve hated your guts,” she replies.

“When you’re working on a script, you’re always dreaming of writing for great actors, and you can’t feed them kale salad,” laughed García. “You have to give them big pieces of red meat that they can feed on. You also must introduce the conflict right away. Kathy’s character is of a certain age and she’s about to have a double mastectomy, which brings out a whole bunch of fear and vulnerability. If the conflict is big, actors will put themselves in it. You don’t have to tell them how big and scary the situation is because it would be that way for anyone. Find a big conflict, introduce it quickly and actors will build on that wonderfully.”

By juxtaposing these tales of alienation, García invites us to draw connections between them, thereby illustrating how mankind is united by our shared yearnings, frustrations and vulnerabilities. A featurette on the film’s DVD shows García and Grobet choreographing the film’s fourth segment, which centers on a couple (Holly Hunter and Stephen Dillane) whose relationship has begun to resemble, in the words of Alvy Singer, a dead shark. While visiting another couple (Isaacs and Molly Parker) at their apartment, the reflection of Isaacs (who we’ve previously seen with Wright) and Parker is visible in a mirror placed behind Hunter and Dillane, enabling the doomed couples to literally mirror one another. According to the featurette, the idea of the mirror was dreamed up on the spot by Grobet, and stands as a key example of the instinctual poetry he expresses visually throughout the film. Among the skilled people behind the camera on “Nine Lives” was the late steadicam operator Dan Kneece, whom editor Mary Sweeney singled out during my conversation with her earlier this year for his brilliant work in David Lynch’s “Mulholland Dr.”

“Dan was a great guy and a very talented operator,” agreed García. “We actually had two operators because the shoot was extremely grueling. They would take turns—two takes each—so the other operator could rest for a half hour or more. We started off with Dan, and on the first day, he was doing a great job, but he was crashing. It’s a stressful shoot because until you have a good take, you have nothing. Sometimes we’d get to lunch and have nothing. We’d have one day to rehearse and one day to shoot. All of the choreography was staged. We rehearsed the first day—first with the actors to find what the blocking was, and then Xavier would start recording the rehearsals on his phone. The operators would record it on their phones as well so that they could get used to it, so by the time we started filming on the next day, everyone pretty much had it down. I wouldn’t dare to do it again, honestly. It was too stressful.”

I will refrain from discussing the final, perfect scene featuring Glenn Close and Dakota Fanning in a graveyard, except to say that it affirms the film’s message that the past causes us to remain frozen in time, and the only way we can move forward is by bidding it adieu. The most dramatic and unexpectedly amusing moments in “Raymond & Ray” also take place in a cemetery, as half-brothers Raymond (Ewan McGregor) and Ray (Ethan Hawke) fulfill the last wish of their father, Harris (Tom Bower), by burying him themselves—with a single shovel.

“It just seems like such a good setting,” García reflected. “First of all, it’s open space, but it’s open space of passions that have already passed. They have been extinguished and don’t mean anything anymore. That’s not an original idea, but the combination of that and the openness of it is what intrigues me. In fact, I was working on a script that has another long sequence in a cemetery just this week, and I thought, ‘My god, are you going to do this for the third time, really?’, so we’ll see. What matters, in the end, are the emotions and the conflict. My whole idea for the story in ‘Nine Lives’ between Robin Wright and Jason Isaacs was the banality of the setting, the fact that it was a supermarket where you don’t expect high emotional stakes to be played out. Obviously, the cemetery as a setting is more loaded with meaning. I like that a supermarket has no baggage, no load. You always know what Robin is thinking or feeling just by looking at her, and the same is true of Jason. They did a great, great job. I always remember her face after he kisses her belly, and it’s like a train just ran into her.”

García’s description of Wright’s astonishing performance recalls the title of his 2000 debut feature, “Things You Can Tell Just By Looking at Her,” and indeed, the same could be said of McGregor’s stunning dual role in the director’s superb 2015 effort, “Last Days in the Desert.”

“You always knew who you were looking at, even though it was the same actor,” marveled García. “You always knew just by looking at his eyes if it was Yeshua or the Devil, and I thought he was excellent in that scene where they speak to each other.”

As for Hawke, García previously served as a camera operator on two of his earlier films, Ben Stiller’s “Reality Bites” and Alfonso Cuarón’s “Great Expectations.” After reading the script for “Raymond & Ray,” Cuarón offered to produce it, just as Alejandro González Iñárritu, who famously experimented with extended takes in “Birdman” and “The Revenant,” served as an executive producer on “Nine Lives.” When I spoke with Guillermo del Toro at Ebertfest in 2016, he said that he felt “Nine Lives” was García’s best film. He also mentioned that he discovered his leading lady for “Crimson Peak,” Mia Wasikowska, in the first season of García’s magnificent HBO series, “In Treatment.”

“I’ve known Alfonso for forty years, since we were twenty,” said García. “I worked with him as a camera operator over the years. I’ve read his scripts and he’s read mine. I’m also very friendly and very close with Alejandro González Iñárritu, though I’ve only known him for twenty years since he moved to LA. Guillermo lived in Canada for a long time, so I don’t see him that often, but he’s obviously a super-talented guy and an example of how you can do genre movies that always feel personal. I read an interview where he said that he doesn’t know how to make a movie without a monster, and then in another interview, I heard him say that he was the monster. So whatever the answers are—and he may not have them—his movies are clearly personal. I know that those three filmmakers are very close—they really are the ‘three amigos’ and I have different relationships with each of them. They do make for an extraordinary generation of Mexican filmmakers, and of course, there are a lot of good directors in Mexico right now, including Carlos Reygadas and Tatiana Huezo.”

One of the chief strengths of “Raymond & Ray” is the pairing of McGregor and Hawke, who complement each other’s approaches to character in endlessly entertaining ways.

“They have different styles,” noted García. “I think for Ethan, it’s all about who and what the character is. It’s all very prepared and thought-out, but he’s more loosey-goosey with coming in and sort of finding the space and getting comfortable with the choices. Ewan prepared everything so rigorously, and it later occurred to me that he kind of prepared for the role in the way that Raymond would’ve prepared to play Raymond. I thought he had a different way of working when I we made our previous film together, but of course, I’m just guessing because each actor has his own process and I don’t ask about it. I just try to see the results fresh.”

The startlingly tense moment when McGregor pulls out a gun mirrors the wrenching vignette in “Nine Lives” with LisaGay Hamilton, whom García cites as one of his favorite actors. I asked him how he goes about directing actors in scenes of such intense emotion.

“The script has to be clear about what the stakes are, and good actors know what the stakes are,” stressed García. “I think it was clear or definitely inferred in that section with LisaGay that she had been abused by her stepfather. Once you’re there and you have that level of hurt—and you bring a gun out, you point it at them and then at yourself—an actor can see that and realize that one of the tragedies of children who are abused is that they sometimes feel it’s their fault, or they may still love the person who is abusing them because it’s a parental figure. Those contradictions are brutal. I think if the conflict is there on the page, then actors will know the level of hurt.”

What makes the director’s work resonate so powerfully, above all, are the details that remain inferred, conveyed purely through unspoken nuance. They leave us with plenty to think about long after the credits roll.

“Some of that is intuitive but I like to do it, meaning that I think there is a difference in movies between things not being clear and things that are mysterious,” said García. “I don’t know myself why Harris asked to be placed naked facedown in the casket. That wasn’t one of the things he did to screw with his sons because he was very adamant about not opening the casket. The fact they discovered him lying that way was only after a turn of events. I also don’t know whether he asked them to dig the grave as a way to punish them or to reward them. But it doesn’t matter because those mysteries are good. I think it’s necessary to have them, and they hopefully don’t impede your appreciation of the conflict. You can’t answer everything.”

Ever since I took my family to see writer/director Rodrigo García’s “Nine Lives” at Chicago’s Landmark Century Centre Cinema per Roger Ebert’s recommendation in 2005, the picture has always had a coveted spot on my top ten list of all-time favorite films. When Alfred Hitchcock attempted to craft a film that would be nearly devoid of cuts in “Rope,” the technique was unheard of in 1948. “Nine Lives” was released a year prior to Alfonso Cuarón’s great “Children of Men,” which demonstrated the visceral power of long takes courtesy of cinematographer Emmanuel Lubezki, whose tour de force achievement foreshadowed the subsequent work that would earn him three consecutive Oscars. In contrast, cinematographer Xavier Grobet’s lensing of “Nine Lives” is much more subtle in its brilliance. Like “Rope,” the film consists of nine takes, yet in this case, each take is a self-contained vignette that follows a woman during a pivotal moment in her life. For decades, “Rope” had been deemed a misfire not only by critics and colleagues, but by Hitchcock himself, who referred to it as a nonsensical “stunt.” Even Donald Spoto, one of the most vital Hitchcock historians, claimed that the long takes in “Rope” contradicted “the basic nature of film itself,” though in The Art of Alfred Hitchcock, he goes on to indirectly illuminate the film’s genius. He mentions “Perpetual Movement No. 1,” the song composed by Francis Poulenc, that is played on the piano by Philip (Farley Granger), a closeted man who committed murder with his lover, Brandon (John Dall), a la Leopold and Loeb. Philip’s former teacher, Rupert (James Stewart), suspects foul play and approaches Philip at the piano, switching on a lamp that serves as an interrogation light. His conversation with Philip goes around in circles, thus mirroring the composition’s repetitious melody. Rupert then turns on a metronome that mechanically ticks down the seconds until Philip inevitably spills the beans. “The song is appropriate, perhaps, not only because the camera is in perpetual motion throughout ‘Rope,’ but because, ironically, the inner state of the principal characters is in an endless cycle of only apparent movement which is in itself a spiritual stasis,” writes Spoto. That sense of stasis is felt by all of the characters in “Nine Lives,” who find themselves trapped in situations that have stagnated their growth. The morning after his latest film, “Raymond & Ray,” screened at the Chicago International Film Festival, García took time to speak with me not only about his new movie, but “Nine Lives” as well. I told him that the latter film demonstrated to me, more than any other, how a short vignette can have the same rich texture and profound impact as a feature, which he affirmed was his ambition with the picture. “You can tell a lot in ten, twelve minutes,” García said. “I see a lot of shorts, especially by younger people, that are impressionistic, but as long as you have the problem in minute one, you have a lot of time.” My favorite scene features Robin Wright as a pregnant wife who runs into her former flame (Jason Isaacs) at the supermarket. As they talk, they settle into the playful rhythms of their past courtship, strolling down aisles that were built for couples to walk down side by side. Yet the coziness turns claustrophobic as Wright awakens to reality, as if breaking out of a trance. When Isaacs asks Wright for her husband’s name, she resists, explaining, “If I say his name to you right now, I won’t know if I’m coming or going.” One aspect of the film that becomes clearer upon repeat viewings is the way in which each woman’s story echoes throughout the surrounding vignettes. The first scene establishes the recurring theme of imprisonment by focusing on a mother (Elpidia Carrillo) in jail. Later on, we see a budding adult (Amanda Seyfried) who is encouraged by her parents to leave home and “spread her wings,” despite the fact that her father (Ian McShane) suffers from a debilitating illness, and her mother (Sissy Spacek) is teetering on the brink of exhaustion. Faced with her childhood home haunted by memories of abuse, a tormented woman (LisaGay Hamilton) exclaims, “This place is a f—king graveyard,” a line that eerily hints at the setting for the film’s final scene. The lyrics of a childhood song Hamilton recites with her sister, “We are made of dreams and bones,” turn up again in the film’s warmest segment, as a patient (Kathy Baker) grows temperamental while preparing for her mastectomy. “I’m so angry with you,” she rants at her husband (Joe Mantegna). “What did I do?” he asks. “I don’t know, ever since I was diagnosed, I’ve hated your guts,” she replies. “When you’re working on a script, you’re always dreaming of writing for great actors, and you can’t feed them kale salad,” laughed García. “You have to give them big pieces of red meat that they can feed on. You also must introduce the conflict right away. Kathy’s character is of a certain age and she’s about to have a double mastectomy, which brings out a whole bunch of fear and vulnerability. If the conflict is big, actors will put themselves in it. You don’t have to tell them how big and scary the situation is because it would be that way for anyone. Find a big conflict, introduce it quickly and actors will build on that wonderfully.” By juxtaposing these tales of alienation, García invites us to draw connections between them, thereby illustrating how mankind is united by our shared yearnings, frustrations and vulnerabilities. A featurette on the film’s DVD shows García and Grobet choreographing the film’s fourth segment, which centers on a couple (Holly Hunter and Stephen Dillane) whose relationship has begun to resemble, in the words of Alvy Singer, a dead shark. While visiting another couple (Isaacs and Molly Parker) at their apartment, the reflection of Isaacs (who we’ve previously seen with Wright) and Parker is visible in a mirror placed behind Hunter and Dillane, enabling the doomed couples to literally mirror one another. According to the featurette, the idea of the mirror was dreamed up on the spot by Grobet, and stands as a key example of the instinctual poetry he expresses visually throughout the film. Among the skilled people behind the camera on “Nine Lives” was the late steadicam operator Dan Kneece, whom editor Mary Sweeney singled out during my conversation with her earlier this year for his brilliant work in David Lynch’s “Mulholland Dr.” “Dan was a great guy and a very talented operator,” agreed García. “We actually had two operators because the shoot was extremely grueling. They would take turns—two takes each—so the other operator could rest for a half hour or more. We started off with Dan, and on the first day, he was doing a great job, but he was crashing. It’s a stressful shoot because until you have a good take, you have nothing. Sometimes we’d get to lunch and have nothing. We’d have one day to rehearse and one day to shoot. All of the choreography was staged. We rehearsed the first day—first with the actors to find what the blocking was, and then Xavier would start recording the rehearsals on his phone. The operators would record it on their phones as well so that they could get used to it, so by the time we started filming on the next day, everyone pretty much had it down. I wouldn’t dare to do it again, honestly. It was too stressful.” I will refrain from discussing the final, perfect scene featuring Glenn Close and Dakota Fanning in a graveyard, except to say that it affirms the film’s message that the past causes us to remain frozen in time, and the only way we can move forward is by bidding it adieu. The most dramatic and unexpectedly amusing moments in “Raymond & Ray” also take place in a cemetery, as half-brothers Raymond (Ewan McGregor) and Ray (Ethan Hawke) fulfill the last wish of their father, Harris (Tom Bower), by burying him themselves—with a single shovel. “It just seems like such a good setting,” García reflected. “First of all, it’s open space, but it’s open space of passions that have already passed. They have been extinguished and don’t mean anything anymore. That’s not an original idea, but the combination of that and the openness of it is what intrigues me. In fact, I was working on a script that has another long sequence in a cemetery just this week, and I thought, ‘My god, are you going to do this for the third time, really?’, so we’ll see. What matters, in the end, are the emotions and the conflict. My whole idea for the story in ‘Nine Lives’ between Robin Wright and Jason Isaacs was the banality of the setting, the fact that it was a supermarket where you don’t expect high emotional stakes to be played out. Obviously, the cemetery as a setting is more loaded with meaning. I like that a supermarket has no baggage, no load. You always know what Robin is thinking or feeling just by looking at her, and the same is true of Jason. They did a great, great job. I always remember her face after he kisses her belly, and it’s like a train just ran into her.” García’s description of Wright’s astonishing performance recalls the title of his 2000 debut feature, “Things You Can Tell Just By Looking at Her,” and indeed, the same could be said of McGregor’s stunning dual role in the director’s superb 2015 effort, “Last Days in the Desert.” “You always knew who you were looking at, even though it was the same actor,” marveled García. “You always knew just by looking at his eyes if it was Yeshua or the Devil, and I thought he was excellent in that scene where they speak to each other.” As for Hawke, García previously served as a camera operator on two of his earlier films, Ben Stiller’s “Reality Bites” and Alfonso Cuarón’s “Great Expectations.” After reading the script for “Raymond & Ray,” Cuarón offered to produce it, just as Alejandro González Iñárritu, who famously experimented with extended takes in “Birdman” and “The Revenant,” served as an executive producer on “Nine Lives.” When I spoke with Guillermo del Toro at Ebertfest in 2016, he said that he felt “Nine Lives” was García’s best film. He also mentioned that he discovered his leading lady for “Crimson Peak,” Mia Wasikowska, in the first season of García’s magnificent HBO series, “In Treatment.” “I’ve known Alfonso for forty years, since we were twenty,” said García. “I worked with him as a camera operator over the years. I’ve read his scripts and he’s read mine. I’m also very friendly and very close with Alejandro González Iñárritu, though I’ve only known him for twenty years since he moved to LA. Guillermo lived in Canada for a long time, so I don’t see him that often, but he’s obviously a super-talented guy and an example of how you can do genre movies that always feel personal. I read an interview where he said that he doesn’t know how to make a movie without a monster, and then in another interview, I heard him say that he was the monster. So whatever the answers are—and he may not have them—his movies are clearly personal. I know that those three filmmakers are very close—they really are the ‘three amigos’ and I have different relationships with each of them. They do make for an extraordinary generation of Mexican filmmakers, and of course, there are a lot of good directors in Mexico right now, including Carlos Reygadas and Tatiana Huezo.” One of the chief strengths of “Raymond & Ray” is the pairing of McGregor and Hawke, who complement each other’s approaches to character in endlessly entertaining ways. “They have different styles,” noted García. “I think for Ethan, it’s all about who and what the character is. It’s all very prepared and thought-out, but he’s more loosey-goosey with coming in and sort of finding the space and getting comfortable with the choices. Ewan prepared everything so rigorously, and it later occurred to me that he kind of prepared for the role in the way that Raymond would’ve prepared to play Raymond. I thought he had a different way of working when I we made our previous film together, but of course, I’m just guessing because each actor has his own process and I don’t ask about it. I just try to see the results fresh.” The startlingly tense moment when McGregor pulls out a gun mirrors the wrenching vignette in “Nine Lives” with LisaGay Hamilton, whom García cites as one of his favorite actors. I asked him how he goes about directing actors in scenes of such intense emotion. “The script has to be clear about what the stakes are, and good actors know what the stakes are,” stressed García. “I think it was clear or definitely inferred in that section with LisaGay that she had been abused by her stepfather. Once you’re there and you have that level of hurt—and you bring a gun out, you point it at them and then at yourself—an actor can see that and realize that one of the tragedies of children who are abused is that they sometimes feel it’s their fault, or they may still love the person who is abusing them because it’s a parental figure. Those contradictions are brutal. I think if the conflict is there on the page, then actors will know the level of hurt.” What makes the director’s work resonate so powerfully, above all, are the details that remain inferred, conveyed purely through unspoken nuance. They leave us with plenty to think about long after the credits roll. “Some of that is intuitive but I like to do it, meaning that I think there is a difference in movies between things not being clear and things that are mysterious,” said García. “I don’t know myself why Harris asked to be placed naked facedown in the casket. That wasn’t one of the things he did to screw with his sons because he was very adamant about not opening the casket. The fact they discovered him lying that way was only after a turn of events. I also don’t know whether he asked them to dig the grave as a way to punish them or to reward them. But it doesn’t matter because those mysteries are good. I think it’s necessary to have them, and they hopefully don’t impede your appreciation of the conflict. You can’t answer everything.” Read More