“Every time I thought something was wrong, I f**ked it up even more.” That about sums up the life of Mike Tyson. There was something about the champ that made every bad situation into something much, much worse. A fascinating athlete, celebrity, and criminal, Tyson seems like the perfect subject for the Craig Gillespie brand of image rehabilitation (or at least magnification) as he has done similar things with complex public figures like Tonya Harding (“I, Tonya”) and Pamela Anderson (“Pam & Tommy”) to great critical success. Gillespie directs two episodes and executive produces Hulu’s “Mike,” and it was created by his buddy Steven Rogers, the writer of “I, Tonya.” Both men seek to knock out arguably their most complex subject to date, recognizing that one can’t tell the story of Mike Tyson without getting into some seriously dark chapters of his life. And the fact that Mike himself has been pretty unhappy with this unauthorized version of his life story almost gives the entire project more credence—maybe it will take some real shots at someone who has gone from a publicist’s nightmare to a carefully crafted comeback story of sorts. However, outside of a captivating central performance, “Mike” stumbles in the TV ring, unable to really pin down its subject in a way that feels more than merely factual.

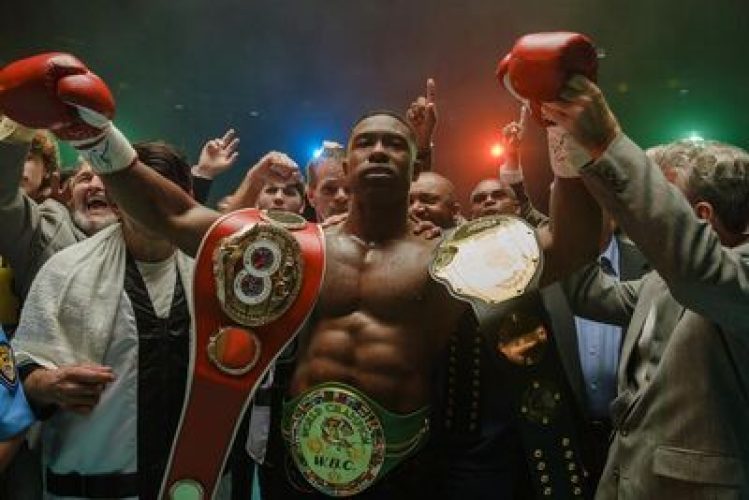

Trevante Rhodes of “Moonlight” stars as Tyson, who doesn’t just narrate his own story, he constantly breaks the fourth wall to do so, both in flashbacks of events from his life and on-stage in a one-man show. For the first four episodes, Rhodes’ undeniable star power gives “Mike” a propulsive energy through the magnitude of his performance, finding the balance of athleticism, rage, and stubborn petulance that fueled Tyson into becoming one of the most famous athletes in the world. Each half-hour episode hits major events in Tyson’s life, starting with childhood, moving through his development under Cus D’Amato (Harvey Keitel) in the second episode, introducing Robin Givens (Laura Harrier) in the third episode, shuffling into the outsized personality of Don King (Russell Hornsby) in the fourth, and then actually handing narrator duties over to Desiree Washington (Li Eubanks) for the fifth episode (and the last one sent for press).

If it sounds like a lot, it absolutely is, and “Mike” is the rare streaming era show that could have been longer. Supporting players in Tyson’s life come off as shallow, especially D’Amato and Givens, although their feeling like devices could be arguably intentional as this Tyson is something of an unreliable narrator. However, they don’t even feel like the exaggerated versions of essential figures in our life that memory often creates. Hornsby pushes beyond this weakness in the fourth episode by imbuing King with enough charisma you may wish the show was called “Don.” Eubanks is excellent in an episode that wrestles with how to tell that vile chapter of the Tyson legacy by literally taking its headline fighter out of the ring.

“Tyson” constantly, and I believe intentionally, calls attention to the story it chooses to tell and who is the one telling it, and it doesn’t always work. For example, the Givens saga gets to the reported violence between the two, although it softens a lot of its impact—visualizing a reported altercation between Tyson, Givens, and Givens’ mother in stylized slo-mo drains it of its dark realism. Tyson himself has often seemed hesitant to reveal the dark energy that often drives him and so it makes a certain amount of sense that “Mike” would have a similar problem, but it leads to a sense that we’ve heard this story before. A lot of it smelled like bullshit then, too.

The constant gamesmanship in terms of storytelling often makes “Mike” more of an exercise in style than something new and insightful. For example, after a fight with Givens, Tyson turns to the camera and says directly that’s the moment when she told him she lost their baby to a miscarriage, and then he repeats it over narration. It’s not from Robin, whose voice is literally silenced by the mix. These decisions are fascinating but mostly in an intellectual sense instead of an emotional one and they are often shallow and showy instead of deepening the legacy of Mike Tyson or shifting the public perception of him. Even the decision to hand the fifth episode to Washington feels like a bit of a copout as if the writers couldn’t figure out what Tyson would possibly say and so they don’t force him onto the hot seat.

Maybe Mike Tyson is too much for a TV series on Hulu. One could seriously take so many chapters of his life and blow them up into feature films from the pigeon-loving kid who was bullied into becoming a champion to the violent predator to the boxing legend to the ex-con who somehow became a comedy star in film and television. Eight episodes of half-hour television isn’t enough for “Mike” to dig deeper than the facts and the show comes off like a series of quick punches instead of the long, complex fight that leaves everyone bloodied in the end. Given how quickly Tyson himself often got in and out of the ring before his opponent knew what hit him, maybe that’s the point.

Five episodes screened for review.

“Every time I thought something was wrong, I f**ked it up even more.” That about sums up the life of Mike Tyson. There was something about the champ that made every bad situation into something much, much worse. A fascinating athlete, celebrity, and criminal, Tyson seems like the perfect subject for the Craig Gillespie brand of image rehabilitation (or at least magnification) as he has done similar things with complex public figures like Tonya Harding (“I, Tonya”) and Pamela Anderson (“Pam & Tommy”) to great critical success. Gillespie directs two episodes and executive produces Hulu’s “Mike,” and it was created by his buddy Steven Rogers, the writer of “I, Tonya.” Both men seek to knock out arguably their most complex subject to date, recognizing that one can’t tell the story of Mike Tyson without getting into some seriously dark chapters of his life. And the fact that Mike himself has been pretty unhappy with this unauthorized version of his life story almost gives the entire project more credence—maybe it will take some real shots at someone who has gone from a publicist’s nightmare to a carefully crafted comeback story of sorts. However, outside of a captivating central performance, “Mike” stumbles in the TV ring, unable to really pin down its subject in a way that feels more than merely factual. Trevante Rhodes of “Moonlight” stars as Tyson, who doesn’t just narrate his own story, he constantly breaks the fourth wall to do so, both in flashbacks of events from his life and on-stage in a one-man show. For the first four episodes, Rhodes’ undeniable star power gives “Mike” a propulsive energy through the magnitude of his performance, finding the balance of athleticism, rage, and stubborn petulance that fueled Tyson into becoming one of the most famous athletes in the world. Each half-hour episode hits major events in Tyson’s life, starting with childhood, moving through his development under Cus D’Amato (Harvey Keitel) in the second episode, introducing Robin Givens (Laura Harrier) in the third episode, shuffling into the outsized personality of Don King (Russell Hornsby) in the fourth, and then actually handing narrator duties over to Desiree Washington (Li Eubanks) for the fifth episode (and the last one sent for press). If it sounds like a lot, it absolutely is, and “Mike” is the rare streaming era show that could have been longer. Supporting players in Tyson’s life come off as shallow, especially D’Amato and Givens, although their feeling like devices could be arguably intentional as this Tyson is something of an unreliable narrator. However, they don’t even feel like the exaggerated versions of essential figures in our life that memory often creates. Hornsby pushes beyond this weakness in the fourth episode by imbuing King with enough charisma you may wish the show was called “Don.” Eubanks is excellent in an episode that wrestles with how to tell that vile chapter of the Tyson legacy by literally taking its headline fighter out of the ring. “Tyson” constantly, and I believe intentionally, calls attention to the story it chooses to tell and who is the one telling it, and it doesn’t always work. For example, the Givens saga gets to the reported violence between the two, although it softens a lot of its impact—visualizing a reported altercation between Tyson, Givens, and Givens’ mother in stylized slo-mo drains it of its dark realism. Tyson himself has often seemed hesitant to reveal the dark energy that often drives him and so it makes a certain amount of sense that “Mike” would have a similar problem, but it leads to a sense that we’ve heard this story before. A lot of it smelled like bullshit then, too. The constant gamesmanship in terms of storytelling often makes “Mike” more of an exercise in style than something new and insightful. For example, after a fight with Givens, Tyson turns to the camera and says directly that’s the moment when she told him she lost their baby to a miscarriage, and then he repeats it over narration. It’s not from Robin, whose voice is literally silenced by the mix. These decisions are fascinating but mostly in an intellectual sense instead of an emotional one and they are often shallow and showy instead of deepening the legacy of Mike Tyson or shifting the public perception of him. Even the decision to hand the fifth episode to Washington feels like a bit of a copout as if the writers couldn’t figure out what Tyson would possibly say and so they don’t force him onto the hot seat. Maybe Mike Tyson is too much for a TV series on Hulu. One could seriously take so many chapters of his life and blow them up into feature films from the pigeon-loving kid who was bullied into becoming a champion to the violent predator to the boxing legend to the ex-con who somehow became a comedy star in film and television. Eight episodes of half-hour television isn’t enough for “Mike” to dig deeper than the facts and the show comes off like a series of quick punches instead of the long, complex fight that leaves everyone bloodied in the end. Given how quickly Tyson himself often got in and out of the ring before his opponent knew what hit him, maybe that’s the point. Five episodes screened for review. Read More